Where Is Pullman, Exactly? A Comprehensive Guide

The word “Pullman” is used to refer to many layered, differently bounded geographies on the far south side of Chicago, all centered on the onetime Pullman railcar factory complex and its adjoining 1880s factory town. A lack of definitional specificity can stymie conversation about the area, since there are often large differences in stewardship histories, socioeconomic conditions, present-day built environment, and historic preservation rules between one geographic definition of Pullman and another. This guide attempts to elucidate the different layers, their roots, and their present-day applications.

The Broadest Possible Definition

The reason we call this part of the city Pullman is because of industrialist George Pullman’s late 19th century project to locate a large factory complex and company town here, in an area that at the time lay outside Chicago city limits in the independent Hyde Park Township (a township which encompassed much of today’s south side).

The famous industrial and residential portions of the factory town made up only a small portion of the total Pullman land holdings in the vicinity. The Pullman Palace Car Company and a related legal entity, the Pullman Land Association, owned large swaths of land west of Lake Calumet around the factory. Those holdings included some portions of present-day neighborhoods (and even south suburbs) that are no longer referred to as Pullman in practically any context, like Rosemoor and Riverdale.

The below map, held in the collection of the Pullman State Historic Site, shows much of those holdings (but notably, not all of them) at some point in the early 1880s. The boundaries of the map depict land holdings stretching all the way from 87th Street down to 138th Street, well beyond what is considered Pullman today by any actively operational definition.

The Pullman Land Association held this large amount of land for many reasons - by retaining full control over its environs, the company and its leaders hoped to ensure the envisioned success of the Pullman factory town experiment. Some of the land was used to supply brick for the company’s buildings, some was used to farm food consumed by Pullman workers, some was sold strategically to supplier firms, some was platted for eventual small-scale private land sales, and most was left empty until the Association lost interest in tightly held stewardship of its factory surroundings following the 1894 Pullman Strike and the death of George Pullman in 1897.

The above map was created when the whole experiment was still quite new, but a small section in the middle of the factory town just east of present-day Cottage Grove Avenue between about 108th Street and 109th Street had already been sold to the Allen Paper Car Wheel Company, a supplier of the Pullman Palace Car Company.

The Pullman Community Area

By the time that the University of Chicago’s Social Science Research Committee collaborated with the Chicago Department of Public Health to define the city’s official “Community Areas” in the 1920s, formal boundaries which have been relatively static in the decades since, much of the Pullman company’s vast land holdings had been sold. Communities around Pullman (like Roseland) had strong identities of their own which subsumed some of the spaces formerly held by the Pullman Land Association, especially west of the railroad tracks that run parallel to Cottage Grove.

However, the Pullman company was still highly active and retained a strong presence in the area. In the first decades of the 20th century the company opened several massive new industrial facilities, particularly north of the original 1880s factory grounds, which solidified the company’s dominance over local employment and defined the area to residents and outsiders alike (albeit in a fundamentally different way than the days of the notoriously tightly controlled factory town that the company had been forced to divest itself from following the 1894 strike).

As a result, the team that defined Chicago’s official Community Areas chose boundaries for the Community Area of Pullman at 95th Street, 115th Street, Cottage Grove Avenue, and a curving edge of Lake Calumet that today corresponds to the meeting point between Stony Island Avenue and the Bishop Ford Freeway. This definition lies entirely within land once controlled by the Pullman Land Association, and includes the core of the original factory town, a great deal of industrial land, and several later residential developments situated on formerly Pullman-controlled land. As seen in the city’s official Community Areas map:

Community Areas, alongside wards and census tracts, are one of the basic geographic building blocks of municipal functions in Chicago. Because they have been relatively stable through time, unlike those other two geographies, Community Areas are often used for longitudinal studies and casual analyses across decades. When you look at reported demographics for Pullman, or reported crime statistics, or other commonly referenced metrics of that nature, you are most likely looking at information that is summarized at the Community Area level.

Contested Notions Of “The Neighborhood”

Citywide, there is a great deal of misalignment between the largely stagnant Community Area boundaries and what people call “their neighborhood” - Back of the Yards and Bronzeville are both examples of areas with strong neighborhood identities which don’t have correspondingly named or bounded Community Areas, for instance. Pullman exhibits a different sort of ambiguity - a corresponding Community Area exists, but that Community Area is sometimes considered overly broad.

A handful of homes and businesses that were not part of the original factory town already existed by the time the Pullman Community Area was defined, built directly adjacent to the factory town and closely associated with it. One such cluster was developed in the first two decades of the 1900s between 103rd Street, 106th Street, Cottage Grove Avenue, and Corliss Avenue to meet housing (and drinking) needs for Pullman workers who would labor within a large new facility planned for the other side of 103rd Street. This image from the archives of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago shows some of that new development as it looked during sewer work in 1917:

After the Community Area map was formalized, the Pullman Community Area continued to evolve. Some new development continued to be closely associated with the Pullman company and with Pullman as a socially defined neighborhood - one example is a series of rowhouses, referential to the original form of the factory town, that were built to house wartime Pullman workers in remaining undeveloped land between 105th and 106th. But two other distinct communities were carved from the Community Area that began to break away from association with the name “Pullman”.

The first of these two, Cottage Grove Heights, is a section of single family homes built for middle class buyers beginning in the late 1930s. Situated in the far northern portion of the Pullman Community Area, it is separated today from the rest of the Community Area by a short east-west stretch of the Bishop Ford. The second, London Towne Houses, is a housing cooperative built by the Foundation for Cooperative Housing in the mid-1960s as part of a Civil Rights Movement-associated wave of interest in community-owned housing. Bucking the standard Chicago street grid, its curving streets occupy the space between 100th Street, 101st Street, Cottage Grove, and the Bishop Ford. This image of the development comes from an article published in the Chicago Tribune in January of 1965:

Cottage Grove Heights and London Towne Houses are not typically described as “Pullman” by their own residents; there are many reasons for this. They are physically separated from other parts of the Pullman Community Area, their residents have historically had different sets of race, class, and occupation characteristics than those in other parts of the Community Area, and since 1961 both developments have been mapped to a different city ward than the rest of the Pullman Community Area (though a small portion of the old factory town was also grouped with them between 1961 and 1986), diminishing opportunities for shared bonds of local political activity to form. However, non-residents often describe both these areas as Pullman, since they don’t map cleanly to any other larger social neighborhood with significant name recognition the way that e.g. Rosemoor maps onto Roseland.

South of 103rd Street, any assertion of a “correct” application of the Pullman name is still quite subjective. Extant housing from the original factory town exists between 104th and 115th (there’s also an extant wooden “Brickyard Cottage” that was moved southwest to 119th Place & Calumet Avenue following closure of the Pullman brickyards in the 1890s, and possibly another in South Shore, but that’s beyond the scope of this guide). By the strictest definition focused on continuity with the 1880s factory town, one could consider those extant 1880s buildings alone to qualify - a later section of this guide outlines the parameters of the relevant formal historic districts. However, it is uncommon outside of preservation-specific contexts to use the word Pullman to refer solely to the original factory town structures without any of the present-day changes and additions to the blocks around it.

As a neighborhood, “Pullman” most commonly refers to the area covered by two census tracts - Census Tract 5002 runs from 103rd to 111th, and Census Tract 5003 runs from 111th to 115th. These tract outlines are reproduced from Census Reporter:

For a variety of reasons, the two census tracts also represent two relatively socioeconomically distinct areas in the present day despite their shared early history. They are sometimes divided into labels of “North Pullman” and “South Pullman” as a result. A full history of the neighborhood divide is beyond the scope of this guide - it involves the Pullman company’s own development and land stewardship patterns, physical barriers presented by the industrial park that sits between the two neighborhood halves, differing racial and economic shifts during the era of blockbusting and desegregation, and several other factors - but the divide is the subject of much contemporary discussion.

On paper, most local organizations currently serve residents on both sides of 111th and define Pullman as anywhere between 103rd, 115th, Cottage Grove, and the Bishop Ford. One notable exception is the Pullman Civic Organization, a longstanding community organization in South Pullman which may one day extend its membership boundaries into North Pullman as a result of a vision process undertaken in 2020.

This divide produces different casual definitions of what constitutes Pullman in everyday conversation. Residents north of 111th nearly universally use the term “Pullman” today to refer to the entire portion of the Pullman Community Area between 103rd and 115th, whereas there is greater variance in the boundaries implied by the word for residents south of 111th. Some South Pullmanites conceptualize “Pullman” as South Pullman alone, and only refer to the northern portion as North Pullman. Others apply the same shared definition as most North Pullmanites. This phenomenon is far from unique among Chicago neighborhoods; another example with similar socioeconomic implications is that of North Kenwood and South Kenwood. The degree of social separation between the two areas, and the frequency with which residents of either have used the separate “North Pullman” and “South Pullman” monikers, has varied over the decades - for instance, in 1990s many North Pullman residents more strongly self-identified by that hyperlocal label, when a locally led group called the Historic North Pullman Organization acted as a North Pullman corollary to the Pullman Civic Organization.

Official Pullman Historic District Definitions

Practitioners in the field of historic preservation are typically more aware than the general public that federal and state landmark designations don’t confer much formal protection upon designated spaces, though they do unlock preservation-focused funding mechanisms for local organizations and individual property owners. Some federal regulations allow for review and modification of projects initiated by (or in collaboration with) federal agencies inside historic places, like Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, but formal protections against demolition, visual modification, etc. are generally set and administered at the local level.

The Pullman National Historic Landmark District encompasses the area bounded by 103rd, 115th, Cottage Grove, and the curving railroad tracks that run from about 103rd & Woodlawn to 115th & Champlain. A similar state-level designation has little to no active effect on its own, but the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency took direct control of the former Pullman company’s main administration building, a portion of its former erecting shops, and the Hotel Florence in 1991 to begin a managed path toward restoration as the Pullman State Historic Site. The state still retains ownership and management of most of that property at the time of writing, but transferred the factory administration building to the National Parks Service when the Pullman National Monument (discussed in the next section) was declared in 2015.

In contrast to largely light-touch federal and state designations, the City of Chicago’s Pullman Landmark District has substantial regulatory weight. It also evidences some of the historic North Pullman/South Pullman divide - the district was initially only composed of the portion of the neighborhood south of 111th, plus the old factory administration building and its erecting shops, as campaigned for by the Pullman Civic Organization and other local stakeholders in response to the threat of neighborhood-scale demolition under city plans to expand industrial land use in the vicinity during the 1960s. That Landmark District was declared in 1972, titled the South Pullman District. In June of 1993, the remaining unprotected original factory town buildings north of 111th were separately declared as the North Pullman District (the result of an advocacy effort by the aforementioned Historic North Pullman Organization), and in 1999 the two districts were combined. This map shows the current Pullman Landmark District, derived from this city-published shapefile:

Unlike the federal and state districts, the city Landmark designation comes with specific restrictions on modification or demolition of any contributing property. Property owners within the district must abide by several regulations related to maintenance and restoration of street-facing elements of their buildings, and all building permits submitted within the Landmark District pass through review by City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development’s Historic Preservation Division.

It is worth noting that the city-level Landmark District does not cover every known original 1880s Pullman building. In addition to the relocated brickyard cottage(s) discussed in the previous section, a row of ~1888 homes constructed by the Pullman company and currently located along the northern edge of 115th Street are not included in the district, and some industrial buildings that were once part of the factory complex are also not included (such as a former brass foundry on 110th Street that is used today by the University of Chicago press as part of their distribution center).

The Pullman National Historical Park

Today, Pullman possesses two very different federal designations. The aforementioned Pullman National Historic Landmark District is longstanding and largely passive in nature, but the Pullman National Monument and its successor legal structure, the Pullman National Historical Park, has existed only since 2015 and has a markedly different purpose. The Pullman National Historical Park has its own, narrower boundary, shown here in a graphic from the “Positioning Pullman” report produced by stakeholder groups immediately following the National Monument designation:

The existence of the Pullman National Historical Park brings with it a set of regulations that apply most strictly to the federal government itself - when federal agencies own property within the Park boundaries, they are held to certain standards of review and cross-agency collaboration to ensure that any projects, leases, or land sales they may undertake do not adversely affect the historic nature of the subject area. The same regulations provide a framework for involvement in local-level planning, but the law largely defers to local and state regulations for specifics.

The Pullman National Historical Park, in terms of strict National Parks Service property ownership, could be said to only encompass the former Pullman company administration building at the time of writing. But in terms of coverage by federal parks regulation, availability of targeted federal funds for partner organizations like the Historic Pullman Foundation and the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum to conduct preservation-related activities, and presence of National Parks Service programming, the Pullman National Historical Park encompasses the entire 2015 National Monument Boundary.

Because evolving designations have interacted through time with an evolving social neighborhood, one of the most amorphous terms in common use locally is “Historic Pullman”. There is no widely accepted definition for this term, or even one or two clear patterns of use. Some speakers use it to refer to the original factory town buildings alone. Some use it to refer to the area otherwise sometimes called South Pullman, since that’s where historic preservation activity initially gained steam in the neighborhood in the 1960s. Some use it to refer to the two census tracts that make up the most commonly held definition of Pullman as a neighborhood, North Pullman and South Pullman. Still others hold a definition essentially coextensive with the Pullman National Historic Landmark District, or with the National Monument Boundary.

Pullman Park, Pullman Crossings, And Other Complications

The Pullman National Historic Landmark District and the National Monument Boundary both cut off on their eastern edge along railroad tracks that once ran through the middle of the Pullman company’s factory. In 1983, a handful of years after the much-diminished Pullman company shuttered for good, one of its successor corporations sold the portion of the Pullman Community Area east of those tracks between 105th and 111th to the Ryerson steel company for use as a steel processing plant.

After the Ryerson plant closed, the land eventually came under stewardship of Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives, who also acquired parcels extending the site north to 103rd. CNI is the master developer for a mixed-use retail, industrial, warehouse, and housing plan on those lands most often called Pullman Park. Public signage in the area declares it as such, though the warehouse portion of the site is also sometimes referred to in commercial real estate contexts as Pullman Crossings. No housing has yet been built on the site, but new retail, athletic, manufacturing, and warehousing uses have been brought online. This rendering, looking southwest, is from Ryan Companies and CNI, co-developers of industrial buildings on the site:

Due to the public prominence of the retail portion of the development, which includes an anchor Walmart and other stores that bring in visitors who otherwise don’t interact much with Pullman, the broader Pullman neighborhood is sometimes now referenced as “Pullman Park”. Though this is technically erroneous, it is not entirely uncommon to hear. Muddying things further, there is also a small public park called Pullman Park at the southeast corner of 111th & Cottage Grove, designated so when given to the city in 1909.

The term “Pullman Park” has some unrelated historic precedent, as well, which persists in legal property records. A section of modern-day Roseland directly west of Pullman between 111th and 115th, once part of the Pullman Land Association‘s holdings in the 1880s, was platted to become a park (now Palmer Park) and residential infill under the name Pullman Park beginning in 1880. This early map was held by the Pullman Land Association and is now part of the collection of the Pullman State Historic Site:

Though the name Pullman Park Addition is still utilized in property records to refer to specific parcels in this section during land transactions, it is not in common use and is largely forgotten outside the context of real estate. There was also a section of present-day West Pullman, now the location of the Maple Park subdivision, which was marketed briefly as Pullman Park during speculative development of the 1880s and 1890s.

But Wait, What About West Pullman?

Even if we zoom all the way out to the Pullman Land Association’s total 1880s holdings, one might notice that none of the areas claiming the plain name of Pullman in this guide are part of the current-day Chicago Community Area of West Pullman. This is because, despite significant linkages in history, West Pullman has never been considered “part of” Pullman by any common definition.

The area known today as West Pullman was formed from several independent villages, towns, and unincorporated settlements prior to annexation into the City of Chicago, as well as later developments during the 20th century. The closest such town to Pullman proper was Kensington, which notoriously held a large number of taverns where Pullman workers could escape from the paternalistically dry Pullman factory town during its early days under full control of the company. During the Pullman Strike of 1894, the strike’s headquarters were located within Kensington.

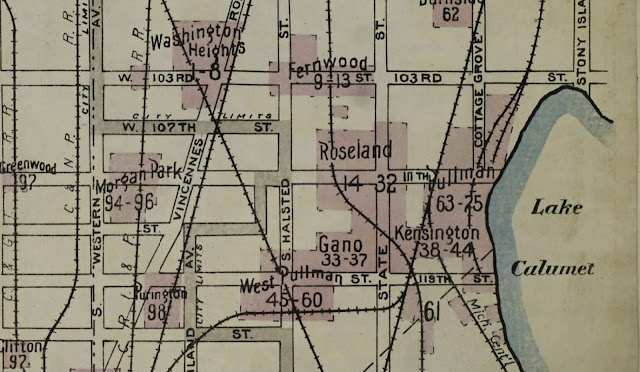

Other settlements in the vicinity during the time of the Pullman factory town experiment included Gano and West Pullman, from which the current-day Community Area gets its name. This map, from the index of Volume E of the Sanborn Map Company’s 1897 fire insurance maps, shows where some of the settlements around Pullman were located at that time:

Established by the West Pullman Land Association in 1891, the West Pullman development had no structural relationship to the Pullman company, but attempted to use association with Pullman (which was a worldwide curiosity throughout the 1880s and early 1890s) to recruit industrial employers and workers to the area. Many Pullman company workers lived in different sections of the modern-day West Pullman Community Area, but it has always retained a separate identity with its own divisions and ambiguities worthy of exploration outside this guide (for instance, Kensington today is the only majority-Latino neighborhood west of Lake Calumet on the far south side of Chicago, and the subdivision of Maple Park is a notable example of a middle-class housing development built specifically for Black families who were denied access to most of the broader neighborhood around it during the mid-20th century).

Pullman and West Pullman touch, just barely, for a fraction of a block along 115th between Cottage Grove and Front Avenue, but West Pullmanites generally don’t consider themselves to live in Pullman and Pullmanites mutually generally don’t consider West Pullman part of their neighborhood. Aside from the occasional overzealous realtor or landlord being nonspecific when advertising a home or apartment, you’ll usually find the two referenced separately.

That said, there is no single, canonical, “correct” definition of what Pullman is and isn’t, or where it is and where it isn’t. There are several overlapping official boundaries, and a whole lot of social context, mostly in passive coexistence and sometimes in active, messy tension with each other. When discussing the area, it is useful to consciously consider which particular geography is in focus, since conditions vary so greatly between one version of Pullman and another that divergent frames of reference can easily mislead or confuse.

Do you have any information to add to this guide, or clarifications/corrections to suggest? Feel free to email me at soren@spicknall.us with your comments.